Worlding a Rhythm with Chila Kumari Singh Burman

Chila Kumari Singh Burman, Hertford Bootle 1970, 2006. NOTE: The artwork features the artist’s fathers ice cream van.

Chila Kumari Singh Burman, a multidisciplinary artist based in London openly speaks about the latent and manifest complexities of her Punjabi-Liverpudlian roots that are examined in her practice. Born and raised in Liverpool, she left home in the late 1970s, and was considerably early in establishing her voice as a British-Asian woman artist, even receiving an honorary doctorate from the University of Arts, London, in 2018. Traditionally trained in printmaking, she subsequently enhanced her skill set by experimenting with various mediums including film, photography and painting that often collectively took the form of installation pieces.

There would be no Britain without us, so I thought of flying the flag for all of us – Black, Asian, Chinese people here…we all make up this country.

Burman unabashedly claims her place of belonging – the UK. Her parents arrived on a ship in the 1950s from Calcutta (present-day Kolkata), the same time as the Windrush Generation who disembarked from the Caribbean. Even though, like many families arriving from ex-colonies, Burman and her family faced racist discrimination, Liverpool and London were as much a home as was the Punjab they left behind. However, engaging with the moment through her work, she prefers to transcend any normative descriptors of the immigrant experience as either ‘in crisis’ or underscored by struggle; and instead, chooses to foreground the way ‘culture’ for her is an embodied experience of creatively exploring Indian iconography and pop art. Burman’s work references and embraces her Punjabi-Hindu background with visual/sensorial triggers of family relationships and pasts – her father’s ice-cream van, the music played by her DJ brother – celebrating the essence of being rooted to a place beyond the definition of diaspora.

Chila reaffirms her rejection of treading a specifically defined British-Asian persona and pushes away from implied post-colonial identity parameters. This is perceivably a way of informing and dismissing assumptions people make about the imagery/aesthetic of her work as a re-looking at her ‘place of origin’. The artist often also appears in her own montages, in the form of self-portraits and other autobiographical traces – the authorial voice like a stream of consciousness oscillates between politics, feminism, family, British racism, Bollywood and Bhangra.

In this conversation, Burman peels away layers of meaning in her practice in order to recalibrate the position from which she wants to be viewed – from the streets of Liverpool to the steps of Tate Britain and beyond…

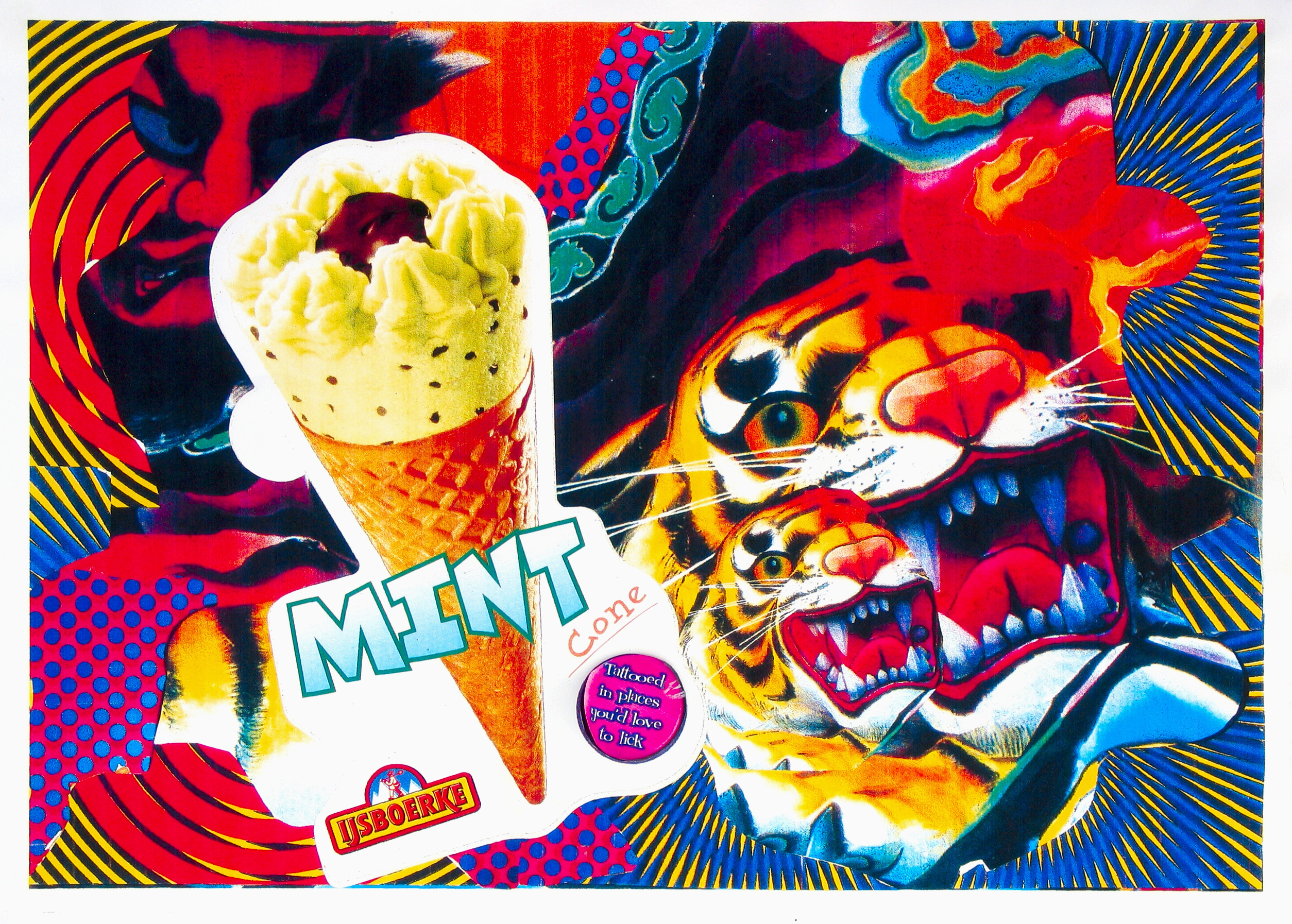

Mint, 2006

Mint, 2006

Veeranganakumari Solanki (VS): Family plays a core role in who you are as a person and artist. There are fragile threads of time, memory and events layered in certain motifs – your father’s ice-cream van and the tiger atop it for instance – that bring back memories of childhood. Accompanied with an emotional charge, they have become key inner references and recurring signposts in your work.

Similarly, in your film about your mother, Kamla (1996), there is this sense of nostalgia gelled with angst. Your father’s prayers that unveil the film, eventually transforms into a rap narrative from “toffee crisps, chocolate and cake, gin and beer” to “Indian films every Sunday afternoon and syrupy sweet masala chai with Durga, Kali and red corduroy dresses”. Do these references explore the duality of being Indian and British? It’s not about separating identity, but perhaps the fluidity and freedom with which you explore and navigate the world around you.

Chila Kumari Singh Burman (CB): Yes, my work is not about exploring my Indian heritage, it’s about celebrating it! Over here (UK), people cannot figure out where I’m coming from. My parents get me, because they are the same as me. Since I was born here, people think I should be ‘westernised’. They are shocked by how ‘Indian’ I am! My father sold ice cream from his van, but when we came home and closed the door, we were in India, we were in Punjab.

People don’t understand because they have never seen our family life behind the door. But I’ve had this kind of assumption about how ‘we’ live all my life, so I am quite used to it. When my parents arrived in the 50s, in their minds, they hadn’t reached Liverpool, and were still living in an India of the 1940s. Sometimes when I tell people that I’m ‘South Asian’, I wonder whether I have to spell out why I am also at ease with speaking colloquial Punjabi and that I went to the mandir every Sunday and even watched Bollywood films while growing up here. What does the term ‘South Asian diaspora’ even mean? It can mean being Sri Lankan, or coming from Pakistan, Bangladesh, England, Canada, America or even Germany and Spain – Indians are all over! Everyone today is talking about systematic racism in the art world and institutions, but this has been going on since the early 1950s! Nothing much has changed.

I am often asked how I became a creative person given the circumstances in which I grew up. I have no idea – we had no books, no crayons, no paper, not even any toys. We were chucked out onto the street after school – English and Asian families alike. We played hopscotch with chalks, three balls and marbles, and sometimes went to the circus and had to help in the ice-cream van. Maybe that’s from where all the colours come into my work. I probably failed a lot of my GCSEs because by the time we cleaned the van, there was not much time for homework, though I always managed Biology and Art assignments since I liked to draw. My art teacher encouraged me to do a foundation course and then I had an excuse to leave home, study art and escape the pressure of getting married at the age of 19! Thankfully, there were family connections in Leeds and London, so I was allowed to go there! So, yes, family is a thread, that has also enabled me to keep up with traditions at home but also artistically grow over time to the person I am.

This test lies in making things difficult for yourself and then finding your way through them instinctively.

VS: This duality which is a part of your every-day may be difficult to accept for somebody else. I wonder how this ‘difficulty’ is communicated to or within you? Its dimensions are layered in your work along with music – from punk in your college years, to the titles you use such as ‘Punjabi Rockers’(2004) etc. There’s always music playing in your studio and it is mixing of sound that sets the narrative strain of your films – be it the rap in Kamla or even your brother’s soundtrack in Dada and the Punjabi Princess (2018).

CB: I listen to a lot of music and use a lot of it too because my brother is a DJ. My film, Dada and the Punjabi Princess has a fantastic soundtrack! My brother knows that I like to hear female vocalists, so he sends me tracks. When I listen, I listen really hard and am in awe with the skill it requires to make these songs. It’s astounding! When people ask me how I make art, I think about the process of music-making. I was watching a documentary on The Beatles – they just play around, write a few lyrics and churn out an entire song that may not be intellectual, but it’s brilliant! Music also comes into my collages and abstract paintings in some way. These pieces are quite hard to do, but they are also probably my favourite renditions because they really push me to think.

VS: The graphic use of words is another facet of your works that transforms the experience of looking at and reading parallelly across imagery. Some of these words are also quite confrontational. In Dada and the Punjabi Princess, groups of words/phrases such as ‘Multiculturalism is coming unstuck’, ‘Whose truth is it anyway’?, ‘…the establishment is not a viable candidate’, and ‘a cover-up for a clean-up’– are enacted through Bharatnatyam, a dance form connected with colonial suppression for being too provocative. How do you go about selecting these words and expressions?

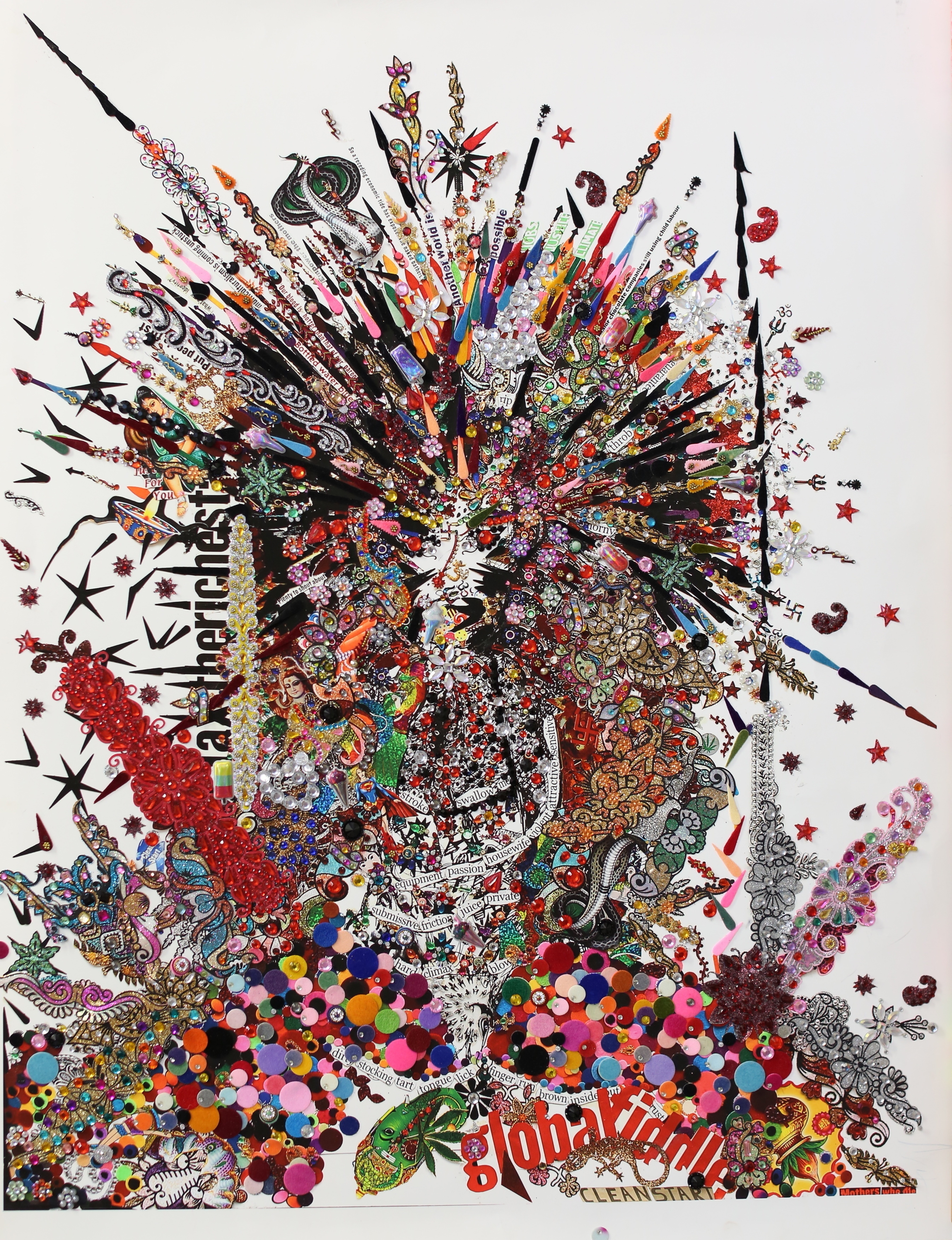

CB: I wrote my dissertation on the Dada school and Surrealism in college, and what interested me about these philosophies were the idea of using the ‘readymade’ – so I work with a lot of bindis and found objects…including words. The actors within these movements however, were largely male. My work however focuses on feminine energy that exudes through the use of colour and kaleidoscopic forms. I sometimes find words and phrases in magazines that I cut up and use like drawings, such as the Bindi Girl series, Remembering a Brave New World (2020), and the White Tiger car (2020). These words are instigators for my audiences to expand and introspect on their meanings and associations.

Dirty Bindi Girl, 2019

Auto Portrait, 2012-18

My work is about me! I create for myself and think of things in layers. I continue to add and expand meaning with associations that connect to my history, objects, feminine forms and situations around me at that moment.

VS: You have used prints, etchings, photos and film for over four decades. The image has also become a departure point with you using your body and self-portraits as essential facets. Can you say more about that?

CB: All I need to find is a good photo, which is the trigger, and I’ll be off! The Auto-Portraits (1996 – ongoing) brings together a number of photocopied images that explore the politics of identity. It’s about the existence of an artist in multiples. Some of the works in this series were real headbangers! But when things are hard, I want to do more of them because it is a challenge. The test lies in making things difficult for yourself and then finding your way through them instinctively. It is the very process that makes me want to finish a work.

VS: There is a sense of seamless flow of thoughts and narratives in your work. This transition is similar to your output and process on canvas where your montage-like executions translate from one medium to the next. These recontextualised forms result in alter-narratives or icons of popular culture such as bindis, ice-cream spoons, glitter, images, martial arts etc. Indian iconography opens up new visual worlds, but under the surface, at a sensory level, there is honesty and humour.

CB: My work is about me! I create for myself and think of things in layers. I continue to add and expand meaning with associations that connect to my history, objects, feminine forms and situations around me at that moment. It is about how I respond to my tradition, gender, women’s empowerment and politics. Louisa Buck, the British art critic explained it quite well in my interview with her for The Art Newspaper. She said my work was an ‘abundance of decoration and embellishment…[and that] I use adornment, but with a message’.

The layers come in quite intuitively. For instance, with the recent Tate Britain commission (Remembering a Brave New World, 2020) I started with the steps of the building that had my iPad drawings; then went on to wrap the pillars with Punjabi Rockers and the doors and other spaces around held neon and other hypervisual drawings with lots of colour. While most of it was planned, the work grew organically. With the imagery, everything there was about me such as my father’s ice-cream van, which had the words ‘We Are Here, coz You Were There’, were reminders of British atrocities and of a colonial past.

There would be no Britain without us, so I thought of flying the flag for all of us – Black, Asian, Chinese people here, we all make up this country. A neon-image of Rani ki Jhansi, who was also printed on the Tate Britain steps, really inspired me with the way she fought the British. I watched the series on Netflix every night while working on that piece. Goddess Lakshmi was a part of the installation to signify the work opening on Diwali and Britannia atop Tate Britain had the words, ‘I’m a mess’ sashed across her while being flanked by Kali, the Goddess of destruction, holding a teacup in her hair together with my signature tiger – all for ‘Remembering a Brave New World’.

VS: In moving forward could you speak about what you would like to leave behind – through ‘Remembering a Brave New World’ (2020) for instance, with respect to the idea of spectacle and spectatorship?

CB: I was so surprised with the number of people who turned up at Tate Britain! It was like a pilgrimage, a party, a 60’s hangout, it could have been Glastonbury! Everyone wanted to be a part of the work and I was thrilled to have created a space for people to gather, dance and just be there with their friends. After the Tate Britain commission, I designed a promo car for Netflix’s ‘White Tiger’ film, which is now part of my vehicle collection with the tuk-tuk and ice-cream van. They all have the tiger on them.

My next works include an upcoming commission for Covent Garden and a Diwali commission for the Museum of the Home. They are going to be focused on animals and women’s empowerment. You’ll see more neon works and I will also be focusing on paintings and etchings. I want my style of drawings to be viewed as a kind of mark-making as I continue to pour myself out and move forward with powerful feminine energy…. something quite magical.

Kamla (excerpt), 1996, Support: Arts Council, England

Dada and the Punjabi Princess (excerpt), 2018

All images and videos, courtesy, Chila Kumari Singh Burman

Photo by: Susanne Dietz

Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) celebrated for her radical feminist practice, examines representation, gender and cultural identity. She works across a wide range of mediums including printmaking, drawing, painting, installation and film.

Born in Bootle to Punjabi-Hindu parents, she attended Southport College of Art, Leeds Polytechnic and the Slade School of Fine Art. A key figure in the British Black Arts movement in the 1980s, Burman was selected as the fourth artist to complete the Tate Britain Winter Commission in 2020. In 2017, she was awarded an Honorary Doctorate and Honorary Fellowship from the University of Arts in London. She has exhibited widely with notable solo shows held at Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA), Middlesbrough; Output Gallery, Liverpool and Tate Britain, London. Her works are also represented in many museums and public galleries including Tate, London; Wellcome Trust, London; British Council; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Science Museum, London and Arts Council Collection, England.

Comments