Age of the Sene – An Interview with Ravi Kashi

Ravi Kashi is an artist and the author of Flexing Muscles, a publication by Reliable Copy.

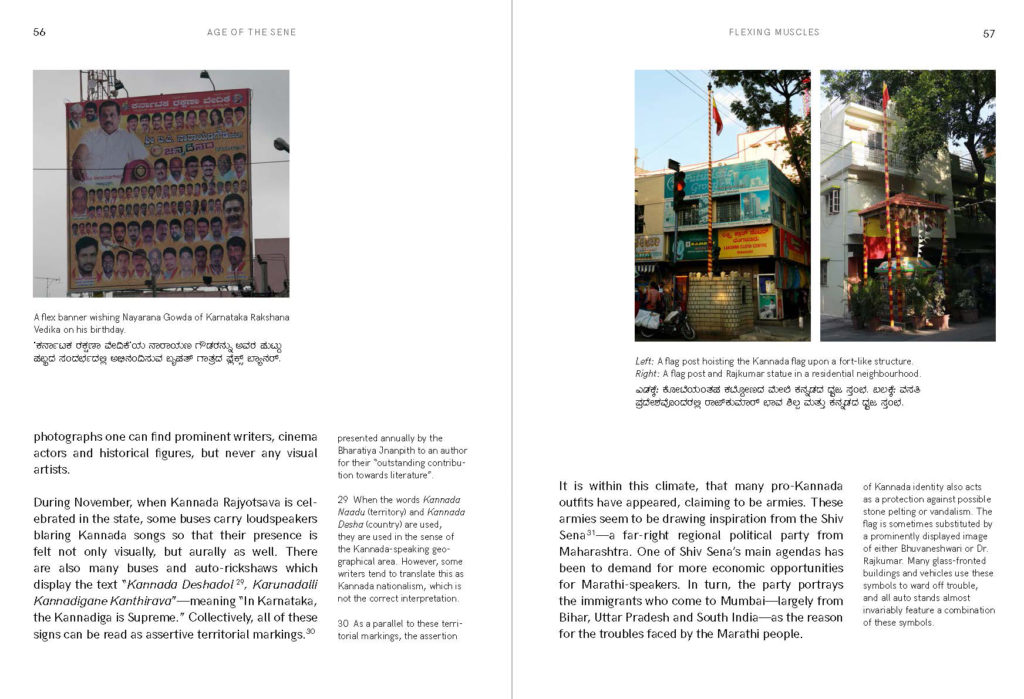

Years of artistic research around the vernacular culture of political banners in Bangalore have culminated in Flexing Muscles by Ravi Kashi, the latest publication by recently established, independent artist-run publishing house, Reliable Copy. These flex banners visualize a vast number of sene (armies) that have been surfacing in the state of Karnataka. Having been formed in the name of safeguarding language, caste/community, and even fan communities for film stars, these sene are announced and re-imagined through these digitally produced hoardings, much like large advertisements. With a bilingual essay (English and Kannada) divided further into five subsections, the book reflects on the medium, their composition and content. Illustrated with photographs taken by the artist over a decade, the essay drafts a portrait of the changing visual culture and essence of Bangalore – one increasingly attuned to aggression and susceptible to vulnerability.

ANISHA BAID: Could you tell us about why and how this inquiry into a unique, visual manifestation around notions of aggression took place?

RAVI KASHI: In hindsight, I can clearly see two threads running through my work all along. The first is an inquiry into the self – into identity, and into questions of who I am. The second was an attempt to comprehend certain ‘animal-like’ qualities – even aggression – in myself and others. These two threads can be traced all the way back to my works as a student. Earlier, it was not a conscious effort but an endeavour to understand something that bothered me deep down. Eventually, it began appearing more prominently, such as in the works ‘Silent Echo’ (2016), and ‘Figure of Speech’ (2017).

‘Silent Echo’, Ravikumar Kashi, 2016

It is also presently the central theme in an ongoing photobook titled ‘Ghar Me Ghuske Maarenge’ (We Will Enter Your Home and Thrash You, 2019). And so, this project started in response to this statement which was made by the Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, during his 2019 election campaign following air strikes in Pakistan. However, as the work progressed, I realized that this kind of passive aggression was manifesting all around us in many ways, and hence became a central part of the work. ‘Flexing Muscles’ (2019) too deals with a form of aggression, by studying the format and content of digitally produced political flex banners in Bangalore.

AB: How and when did you start looking at these political flex banners and dissecting their visual language?

RK: Since 1994, I have been regularly giving talks about art appreciation. In these talks, I use a variety of material to explore the interconnectedness of visual language across various domains. Images seen in public space, such as posters and banners, were one such set of materials which I talked about. In 2004, I purchased a digital camera which completely transformed my relationship to photography. On the other hand, in my paintings I was already drawing heavily from advertisements, and soon, also from the photographs that I had been taking. While sourcing additional material for my paintings, I came across torn posters which quickly became integral to the work. Gradually, I also began to notice flex banners which had started to become more and more common.

By 2013/14, the density of such banners increased, and I continued to document them. By mid-2016 the phenomena of forming senes or armies (local militant groups) became quite popular, and these groups began using flex banners to advertise and announce themselves. I found these groups, along with their modes of public expression interesting, as they were acceptable models of the aggression seen across the nation. When I had collected enough material, I began to organise my notes and observations around these banners, and this led to two public lectures and eventually to this book.

AB: Since this research into flex banners as ‘vernacular culture’ has taken many forms, we’d like to know more about how the book came about?

RK: I would not use the word ‘research’ in a formal sense for what I do since I don’t have the academic tools to do that. No theoretical framework or methodology is followed, and I have never formally studied visual culture. My approach is observational, and my experiences as an artist and exposure to art history have generated my insights. Primarily, it is because I am fascinated by vernacular forms of culture around me, and because I persist to understand them – these works and studies emerge of their own in time.

Spreads in English and Kannada from ‘Flexing Muscles’

Accordingly, this study of flex banners should be located in a larger context as it is not an isolated subject. The flex banners respond to other forms of culture around them – such as the various Kannada-specific markers visible across Bangalore, vinyl stickers on vehicles, advertising, and many other forms both common and vernacular. Since the banners are produced digitally, and are made possible through the tools available through computer technologies, they also share similar formal possibilities with many other forms. They borrow strategies and arrangements from previous forms of visual culture developed via Hindu mythological painting, Independence era posters, and cinema for instance, to express themselves. The book thus came about, when Reliable Copy approached me to bring together my notes and observations on the subject and it was then developed over a year, following many working conversations.

AB: As you mentioned, along with the book, the research also translated into “Silent Echo” and “Figure of Speech”, both works that strongly express themselves through their material qualities; could you tell me more about your process in conceptualizing and creating this work?

RK: In the work, ‘Silent Echo’, which was a large installation, I placed a megaphone on a TV which featured protruding tongues instead of a screen to denote the tone of public debates today. Later, in 2018, I was invited to be in a group show which had an open ended brief of exploring material and meanings it could generate thereof. So I decided to expand on the thread of the megaphone as an image, and I created it in many different materials to see how far I could push the form as well as the idea. Since I had been primarily working with paper for almost a decade, I saw in this work an opportunity to expand my exploration into various other materials. The final work that resulted from this ( titled Figure of Speech) presents nearly fifty different material forms, each with its own distinct evocation and context. Each material functions as a visual metaphor for a certain kind of voice, and naturally my concerns of growing aggression also got reflected in some of the choices I made about how to show it.

‘Figure of Speech‘, Ravikumar Kashi, 2018

AB: A large portion of the present book is about the vernacular culture of Karnataka, and situates your insights about aggression in the very specific political contexts of Bangalore city. However,having attended one of your presentations on the subject, I remember you saying that similar symptoms of rising aggression can be seen across the country. How do you associate these more local and specific insights with the broader political situation in the country?

RK: Over the last few years there has been a shift in the way views are exchanged. Earlier, if somebody proposed an idea or a viewpoint, another would write an article contesting the idea with their own arguments. Now it is a different situation. If I don’t like what you say, I will not use speech to counter it, but use aggression to silence you. This use of ‘force’ is worrying. Earlier, it was during elections that these scenes would heat up and abate, but now it has become the new normal.

The sene that are cropping up in Karnataka are created not just to propagate, but also to enforce certain ideas, and they do not hesitate to use violence towards this end. While one can empathize with the anxieties and vulnerabilities that resulted in the formation of these groups, the tenor of their voice, or the methods they use to ensure they are heard are troubling. Anxieties about unemployment, loss of culture, and of the ‘other’, are being experienced and expressed across the country.

With tools such as computers and digital printing available now to anyone that requires them, these and other similar groups are able to express their anxieties, and also their rage, through mediums and formats that have become cheaper and easier to produce and deploy. As such, the flex banners studied in this book become simply one format in which these symptoms can be witnessed, but point towards a larger trend of intolerance visible across the country and through other forms of emerging vernacular culture.

AB: The book provides many key insights into reading public culture that might be taken beyond flex banners into other forms of cultural expression. Where do you think this language and optics of aggression is going to escalate to? And what might come after this language is exhausted?

RK: I think the language of aggression has already escalated quite a bit. As of now, while it is only manifesting in small incidents or sporadic instances of violence that appear unconnected, if one can actually connect the dots then a larger picture emerges. Our country has lost its faith in conversation. It is now about stating in a loud voice ‘this is who I am and I don’t care what you think’. Conversation entails listening and empathy, both are lost to a large extent.

A few years ago, I had read an essay by U.R. Ananthamurthy titled ‘Matu Sota Bharata’(loosely translated as the ‘India That Has Lost Faith in Words’) which gave me significant insight into our ongoing events. When one can’t convince an adversary about one’s ideas in a gentle, civil manner, the trust in words as a tool to effectively communicate is lost, resulting in a search for other avenues. This can be seen even in the Parliament where instead of debates and discussion, people storm out or even become physical. In Sanskrit there is a saying ‘Yathaa Raja Tathaa Praja’ – ‘As is the King, so are the Subjects’ – and this sums up our times.

‘Engaging Buddha’, Ravikumar Kashi, 2010

Ravikumar Kashi is a an artist working with different mediums such as painting, sculpture, photography and installation. His love for learning and his social concern is translated into his art practice. At the core of his artwork, lies his interest in exploring the mechanics of making meaning. Kashi was born in Bangalore in 1968. He has a Bachelors in Fine Arts, Bangalore University and a Masters in Fine Arts in Printmaking, M.S. University, Baroda and Masters in English Literature, Mysore University, in 1995. His works have been shown internationally in various Museum shows, Biennials, Art Fairs and galleries. He has won many awards including the National award and Karnataka Sahitya Academy award for his writing. He also teaches and writes on art. He has also been featured in the PIX issue Imaginaries – to see more, click here.

Comments