Discussing Photography in India: From Archives to Contemporary Practice

One of the primary concerns of photography in India today is whether pedagogy can enable the practitioner to develop critical objectivity or perhaps an objective critique within an institutionalised image-discourse and a yet to be debated, canonised digital world. A recent publication suggests that significant shifts in production and reception have occurred, but we may also ask whether practice and pedagogy have in fact worked in tandem to trace a history that extends well beyond locational contextualisations or regional specificities mandated by the established domains of the documentary and the evidentiary?

In the last decade, we have witnessed the steady rise of exhibition-related literature, mainstream monographs and online writing of individual practitioners and their histories, enabled through newly-formed archives (private and museum-led), focussing on both vintage and modern/contemporary strands. In one of our previous posts, artist Sunil Gupta, speaks of a growing international interest that has gradually permeated ongoing debates around viewership and currency, but the future of photography still demands further depth and range with regard to questions of inclusivity, assessment and interpretation. With limited critical writing but an enlarging field of practitioners and taught courses, the appreciation of the medium now seeks a forceful re-engagement—one that must claim its place in media studies, which melds the interactive fields of technology and art; sociology and aesthetic theory.

Pablo Bartholomew talk at the MEP, Paris, in conjunction with the exhibition, Affinities. 6 September 2017 – 15 October 2017

Pablo Bartholomew talk at the MEP, Paris, in conjunction with the exhibition, Affinities. 6 September 2017 – 15 October 2017

Raghubir Singh exhibitions have been travelling internationally the last year in particular. After a show at the Met Breuer, it is currently being installed at the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto) till 21 October 2018

Raghubir Singh exhibitions have been travelling internationally the last year in particular. After a show at the Met Breuer, it is currently being installed at the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto) till 21 October 2018

This week, in a written interview with editors, Aileen Blaney and Chinar Shah, we discuss their recent book, Photography in India: From Archives to Contemporary Practice (Bloomsbury, 2018), an anthology of articles which explore an evolving scholarly discourse around a medium in constant transition. As noted in the introduction—the book’s bifurcation into two sections, the historical and the contemporary reveals the ‘gravitational pull between archives and scholars’. The book’s approach to the historical does not look towards colonial archives as monoliths to establish a chronology of photography’s history in India but instead critically engages with issues of partiality and representation within those archives.

The section engaging with contemporary practices in India, discusses recent and ongoing photographic practice and trends while tracing its evolution in the field of education and the visual arts. As professors, both Aileen and Chinar acknowledge recent developments wherein, due to the growing demand from students that live in a media saturated world, the focus of education too is shifting from skill-enhancing instruction to a more in-depth theoretical one which tackles notions of intention and form if not citation and cross-referencing. With a focus on how curricula may change as well as the expectations of new practitioners, our most recent issue titled PIX: The Student Issue, attempted a brief overview of photography courses within and outside university departments.

The need for a publication like Photography in India as noted by artist and instructor, Anna Fox in her Foreword stems from a growing necessity to rethink scholarship around India’s photographic past which has been confounded in colonial history writing and a certain kind of stereotyping, and has hence mainly emerged from the west, looking east, and very rarely thinking of the immense influence of practices in the east which proliferate the west—which has also been debated in South Asian departments in the west over many years. The idea of cultural flow and and historical arcs within lens-based practices therefore demands further scrutiny.

Fox also sees this publication acting as a catalyst for writers, practitioners and other scholars, on the fundamental question of what is a photograph? And extendedly, we may ask, what is the place it occupies in the Indian context, especially when questions of affiliation, belonging and indeed ethics, are still being grappled with. Perhaps the following editorial comment from the PIX: The Student Issue, could be revisited as a point of engagement and concurrence with this subject.

What is the unique character of ‘South Asian’[in this case, ‘Indian’] photo-practices today, taking into account the subcontinent’s particular histories? What is the value of such uniqueness when digital technology has radically altered our experience of the world, reconfigured the dimensions of both viewed subject and viewer subjectivity, as well as the definition of ‘public’ and ‘private’, and indeed the very logic of time, space and causality — enabling us to be instantly everywhere and nowhere, since all image-frontiers can be freely trespassed and all image-horizons seamlessly infiltrated?

Interview with Aileen Blaney and Chinar Shah

How do you position photography from India in a global context?

Aileen Blaney: The idea that photography is everywhere has more critical purchase than ever before – and this is reflected in the diverse set of practices associated with photography brought together in the book’s second section—Photographies in Contemporary India. How people see and experience the self and sociality with the support of photo-synced visual technologies, such as the smartphone, signifies a colossal shift in how subjectivities are being lived out in the contemporary moment, in India and beyond. Furthermore, such profound changes to the media environment, including the internet’s role in saturating our devices with image updates and feeds, have changed how and where we see traditional documentary and photojournalistic images, and which of course in turn have themselves adapted to the newer conditions of image production and networked consumption.

What is the central focus of the book, i.e. which aspects of photo practice have you laid stress on, or is it an overview of all known practices?

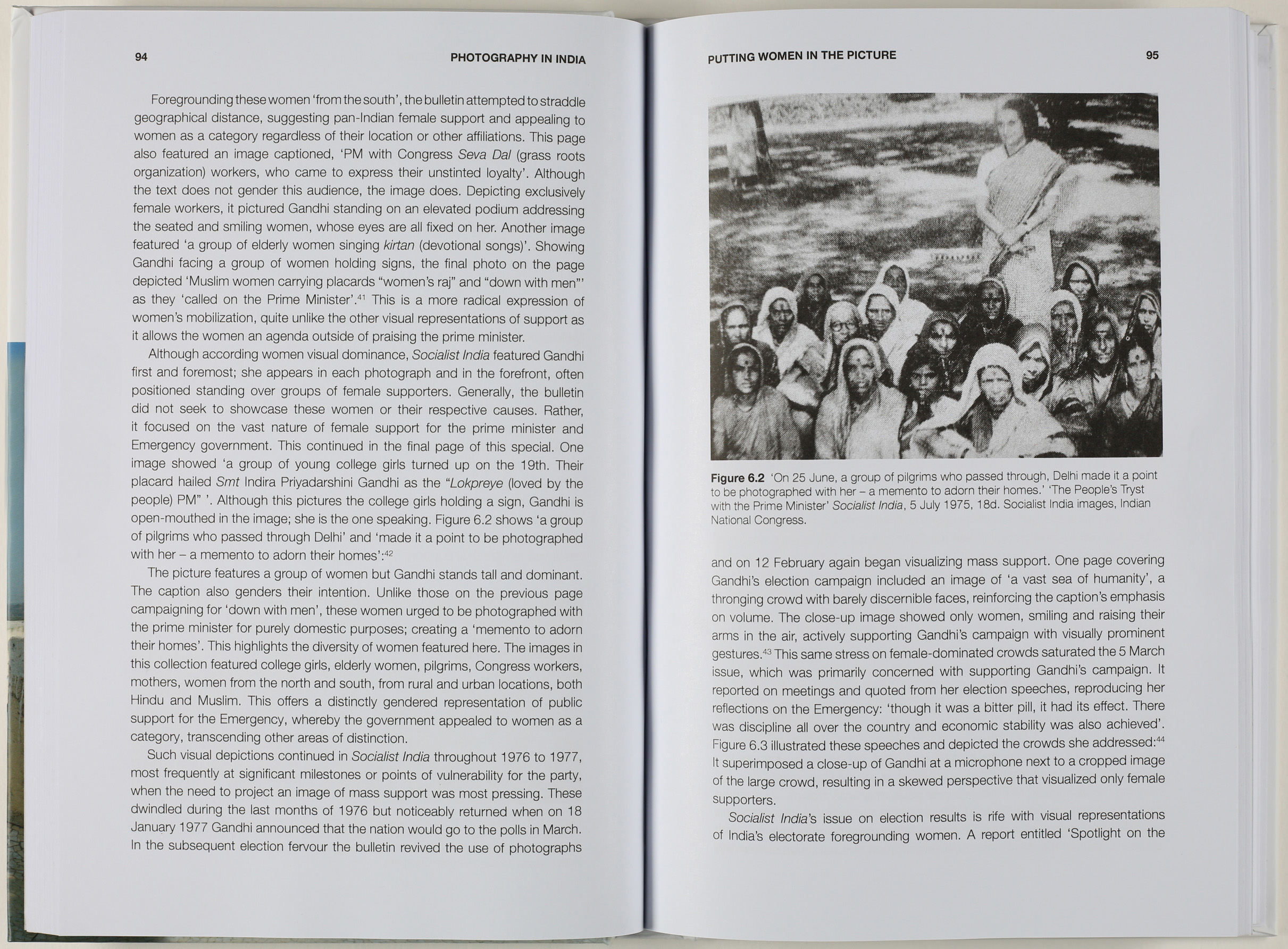

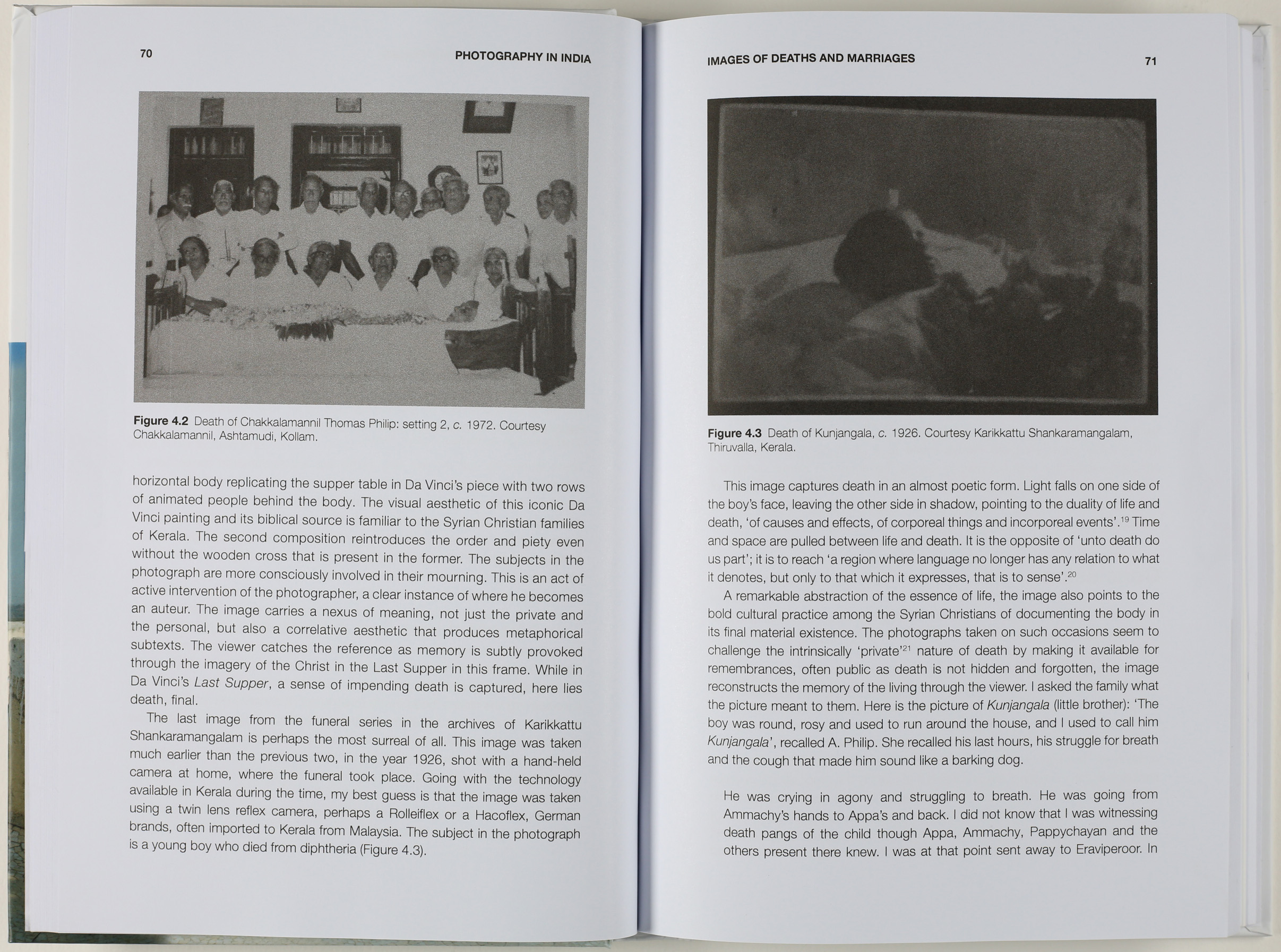

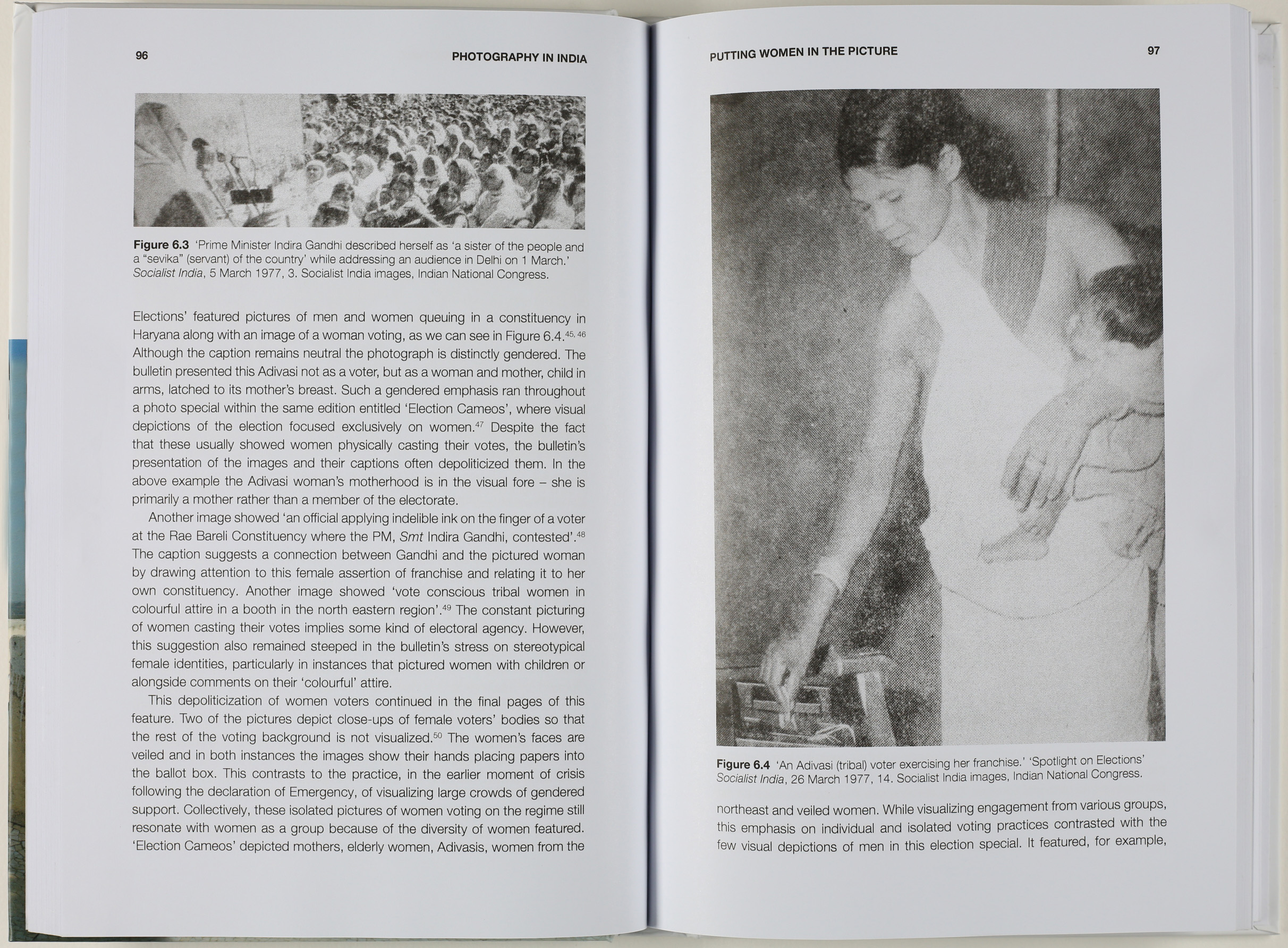

Chinar Shah: The book focuses on two major aspects of photography in India as the title suggest: memory and contemporary practices. Though photography arrived in India soon after its invention, there is an evident lack of contemporary readings of ‘photographies’ from the past. India’s photographic past is lost in the attics of photo studios, personal collections and Government archives. Apart from some of the recent efforts at engaging with the archival material, it may be safe to say that India has a very fragmented photography history. In light of this, it was important to focus a section of the book on various archives and offer contemporary reading of it. Sabeena Gadihoke writes about Homai Vyarawalla’s fashion images and offers a reading of the Nehruvian era and a newly independent India from the perspectives of these images. While Vyarawalla is much known for her work in journalism, the essay offers a fresh perspective on her life, photography and a certain social make up of that time. At the same time, Pooja Sagar talks about images of marriage and death in Syrian Christian family archives. Other essays deal with artistic engagement with photographic archives, performance of the past in the contemporary practices, images of women in visualising the Emergency and photography from the colonial era.

Spread from the book. Image accompanying headline reads The People’s Tryst with the Prime Minister, 5 July 1975, Socialist India.

Spread from the book. Image accompanying headline reads The People’s Tryst with the Prime Minister, 5 July 1975, Socialist India.

Spread from the publication. Images from the Syrian Christian family archive

Spread from the publication. Images from the Syrian Christian family archive

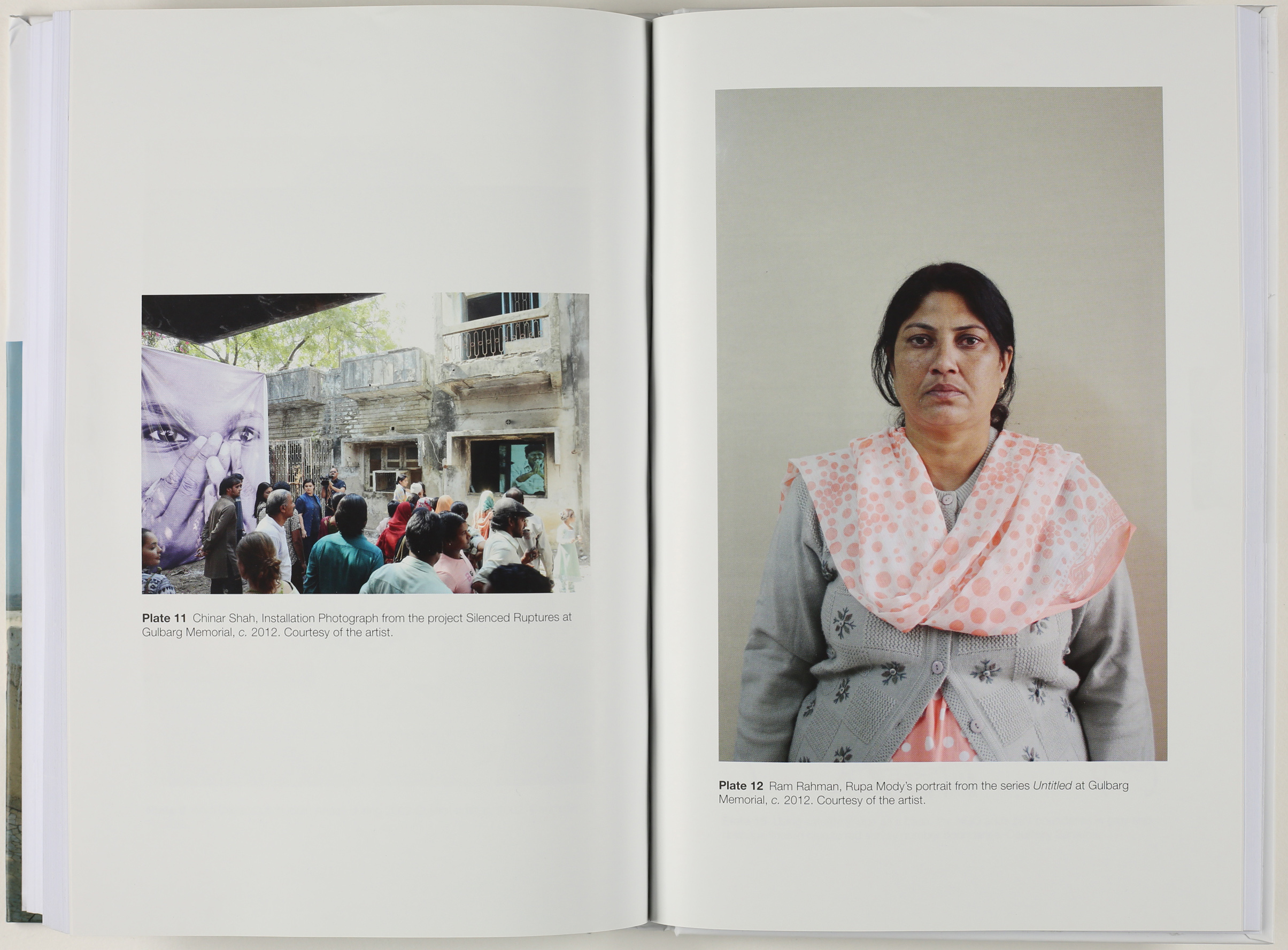

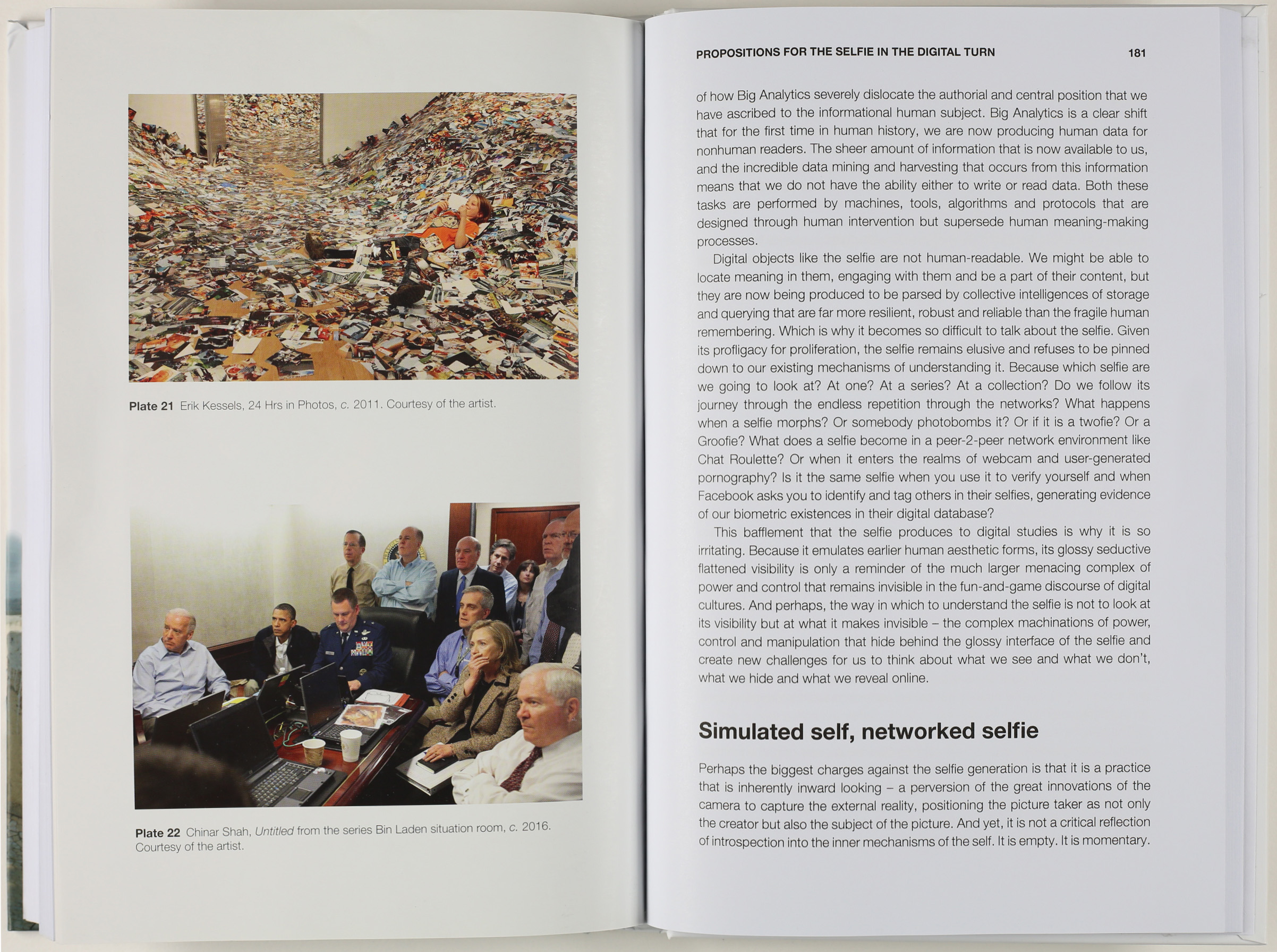

The other section of the book deals with contemporary practices in photography and offers a reading of various kinds of image based works. There is very little scholarship out there that engages with contemporary Indian photography in its complexity. This section is a small effort at addressing this. Nishant Shah in his essay theorises notions of the self in times of the selfie and digital spaces, while Muthatha Ramanathan looks at satellite images and their effects on agriculture policies. Other essays deal with various aspects of contemporary photography from images of the 2002 Gujarat riots, to social documentary practices that go beyond the scope of the camera.

Spread from the publication. Images by Chinar Shah and Ram Rahman

Aileen Blaney: Far from mapping all known practices, the book joins a growing conversation around photography’s history and contemporary photo-based practices in the Indian context. Given the prolific status of photography – its centrality to social media today and its historical role in fields as diverse as science, medicine, criminology and art to name but a few – allied with the book’s modest 200-page length, the book’s contours are not those germane to the map or encyclopedia. Given a multiplicity of directions open to any book centered around photography, we used responses to our call for papers to devise two axes that would lend an organising logic to the book – one focusing on engagements with archival material and the other on a diverse range of contemporary practices.

The book’s first half is devoted to writing on 19th and early to mid 20th century photography in India. Rather than providing an overview or history of photography in India, it demonstrates that histories of photography are as multiple as the sites in which the medium has been put to use – domestic, artistic, administrative, media related (from cartes de visite to photojournalism), colonial, governmental and so forth. As all this suggests, tracing the development of and significance of photography in India across an extended historical period becomes a quixotic affair. That is not to say that piecing together chronological accounts of photography’s development as a technology and social practice in India is not worthwhile and a valuable resource for students, academics, museum professionals, curators, a general readership and so on.

However, in this section of the book, we were more interested in enabling contributors to bring disparate but nonetheless fascinating archival images into a contemporary forum of discussion. In this way, the first half of the book is closer in process to archaeology than to history’s disciplinary protocols – photographs are unearthed, identified and interpreted in informed ways for a larger audience. As editors, we didn’t want to forcefully patch together this diverse set of ‘digs’, or chapters, for the sake of constructing a unified historical narrative (a task that would necessitate a lot more archival material than at our disposal via the modest 100-odd-page section of an edited collection with multiple writers) but we did chapterise the book chronologically to aid the reader’s progression through each of the sections.

While some of our ‘archaeologist’ contributors are interested in situating photographic artefacts in their proper historical contexts, others are interested in philosophically inquiring into how archival images accrue meanings throughout their long lifetimes. For example, Sabeena Gadihoke looks at what a set of un-exhibited photographs from the Homai Vyarawalla collection can reveal about how leisure time was spent among local and expatriate elites in New Delhi of the 1950s and 60s. These images open onto a history markedly different to what is evoked through photographs of political events and leaders through which Vyarawalla made her name as a photojournalist. Raqs Media Collective, by contrast, explore what it means to stage India’s first known war image as part of a multi-media performance for a contemporary audience – opening the section with this chapter was a way of drawing attention to how historical images provide traces or evidence of a past and at the same time are resources for artistic and intellectual inquiries rooted in the contemporary moment.

The archaeological metaphor can be extended to appreciate how Gemma Scott’s chapter in its investigation of highly gendered images of women used in mobilizing support for the Indian Emergency (1975-77) can sit alongside Pooja Sagar’s reflective account of images of deaths and marriages taken by members of an extended Syrian Christian family in Kerala. This chapter examines photographs taken at three different historical junctures – the 1920s, 50s and 70s – from the point of view of their materiality as artefacts from the past and vehicles of memory in the present. In various ways many of the chapters reflexively operate with an idea of photographic time that stresses how contemporary viewing positions’ inflect historical images. This might seem obvious to anyone, i.e. that it is our standpoint in the present that frames what we see in archival photographs. However, the ways in which contributors variously theorise the unique temporality of photography is what makes them so engaging to read.

Spread from the publication. Images from Socialist India

Spread from the publication. Images from Socialist India

Fashion show at the British High Commission, New Delhi, c. 1960, Homai Vyarawalla. Alkazi Collection of Photography

Fashion show at the British High Commission, New Delhi, c. 1960, Homai Vyarawalla. Alkazi Collection of Photography

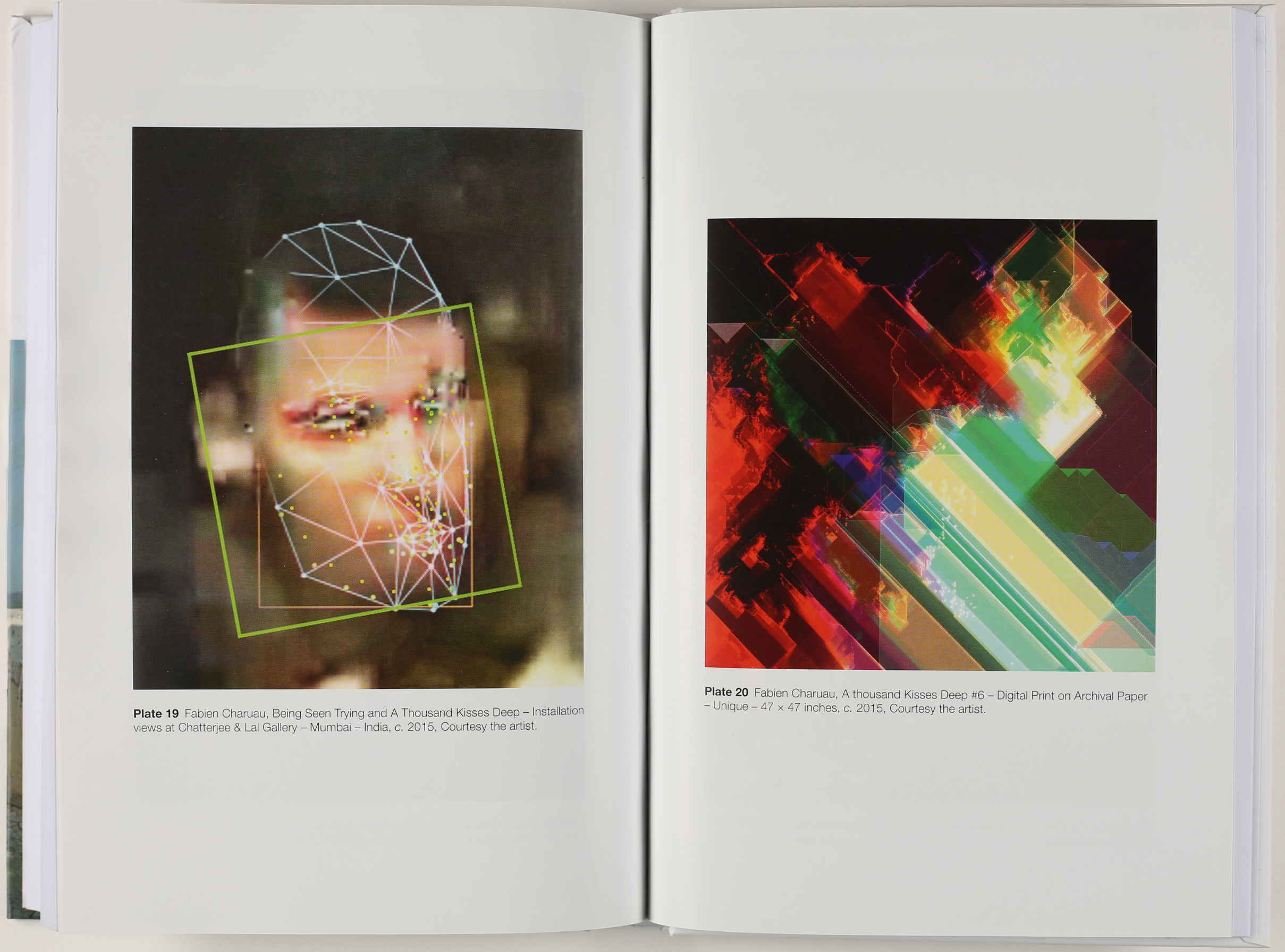

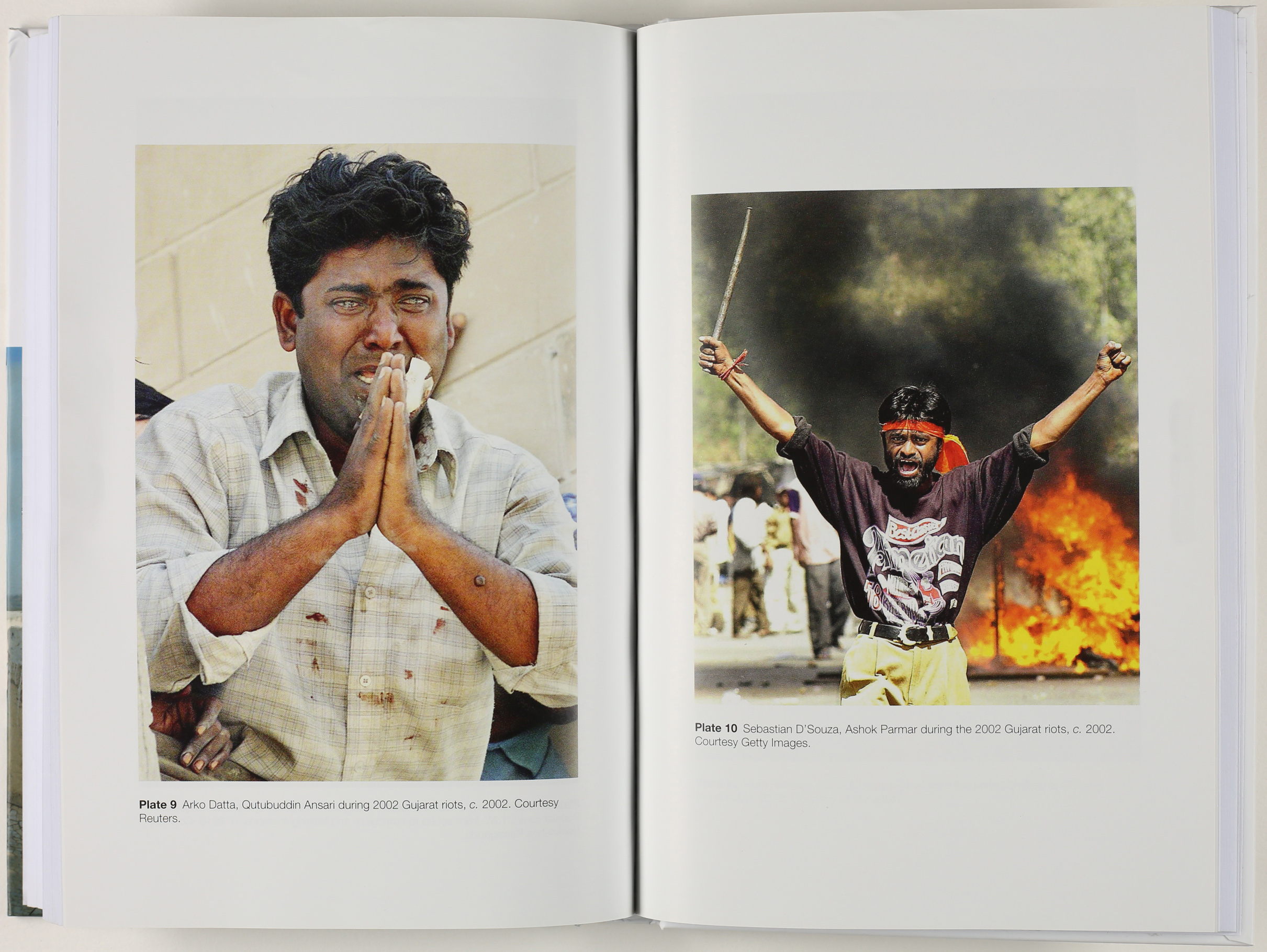

The second section of the book nods at the many hats worn by photography in contemporary India. The chapters bring into focus photography’s range and ubiquity in the country’s visual culture. To underline the pervasiveness of photographic images and technologies across multiple sectors, urban settings and rural contexts, we have included essays in the following areas: how satellite images of agricultural land in North Karnataka can transform approaches to soil conservation interventions, even while issues of access limit the ability of NGOs, working in this instance on a watershed development project, to unlock the knowledge available in dense, multi-spectral images; alternative documentary approaches to portraiture coming out of rural India; how the state uses documentary landscape photography to construct an identity for a new state; violence inflicted by photojournalism on the survivors of communal riots; how the Selfie can be used as a case in point to understand photographs as not only images but as networked data objects – an area of inquiry taken up in another chapter’s investigation of the co-existence of an image’s visibility and the invisibility of data embedded in the image file; and finally, how considering that the internet is at once replete with images and a highly controlled visual space, what is excluded or censored from web space – what in Joan Fontcuberta’s phrasing are the ‘missing images’ – can perhaps tell us the most about what the state wants us to know, think and see.

Spread from the publication. Images by Fabien Charau

Spread from the publication. Images by Fabien Charau

To what extent do you think photography in India that is taught at University, responds to social change?

Chinar Shah: At Srishti, the context of social change is very much part of the curriculum. Within photography, social documentary is often considered part of the understanding of social change. By virtue of engaging with social issues, photography is automatically assumed to fall within the realm of social change. However, photography teaching at Srishti is much more complex and does not encourage such understanding of photographic works.

Students constantly engage with their own socio-cultural surroundings to make work. These changes are often also technological and it is imperative that they are reflected in photography education. It is not possible to teach photography with some kind of nostalgia for the past in terms of the form, technique and visual language. Photography is moving beyond a traditional understanding of image-making and needs to be incorporated to respond to what you would call ‘social change’.

What are some of the theoretical underpinnings of the book?

Chinar Shah: Visual literacy is one of the urgent needs of contemporary times and the book offers different ways of reading photography in India. India is imagined not within the popular representation of its ‘exotic’ visualisation, but has been explored through the complexity of its colonial past, archives, technological advancement, communal tensions and new socio-political circumstances.

Aileen Blaney: Since the book is a collection of essays, it’s impossible to pin it down to having any one distinct theoretical approach. Each chapter theorises its own ground of inquiry and so what we have are theoretical trajectories running in parallel but which nonetheless resonate with each other in their common attention to photography in India. However, the book as we conceived it has a critical thrust and that is to galvanise existing debates around photography in India and to start new ones at a time when photography is more ubiquitous than ever. As I mentioned earlier, the book’s bifurcation into two sections unraveled as both a taking stock of photography in India today and acknowledgement of the gravitational pull between photography archives and scholars in the current moment. When we put out our call for papers, there was an overwhelming rate of responses to the invitation to engage with archival images. This made very real and immediate Michel Foucault’s ‘archive fever’ or the ‘archival impulse’ that Hal Foster describes as driving so many artists, theorists and writers to work in archives, and which has only increased with the seemingly unlimited archival capacities of web servers in locations around the world.

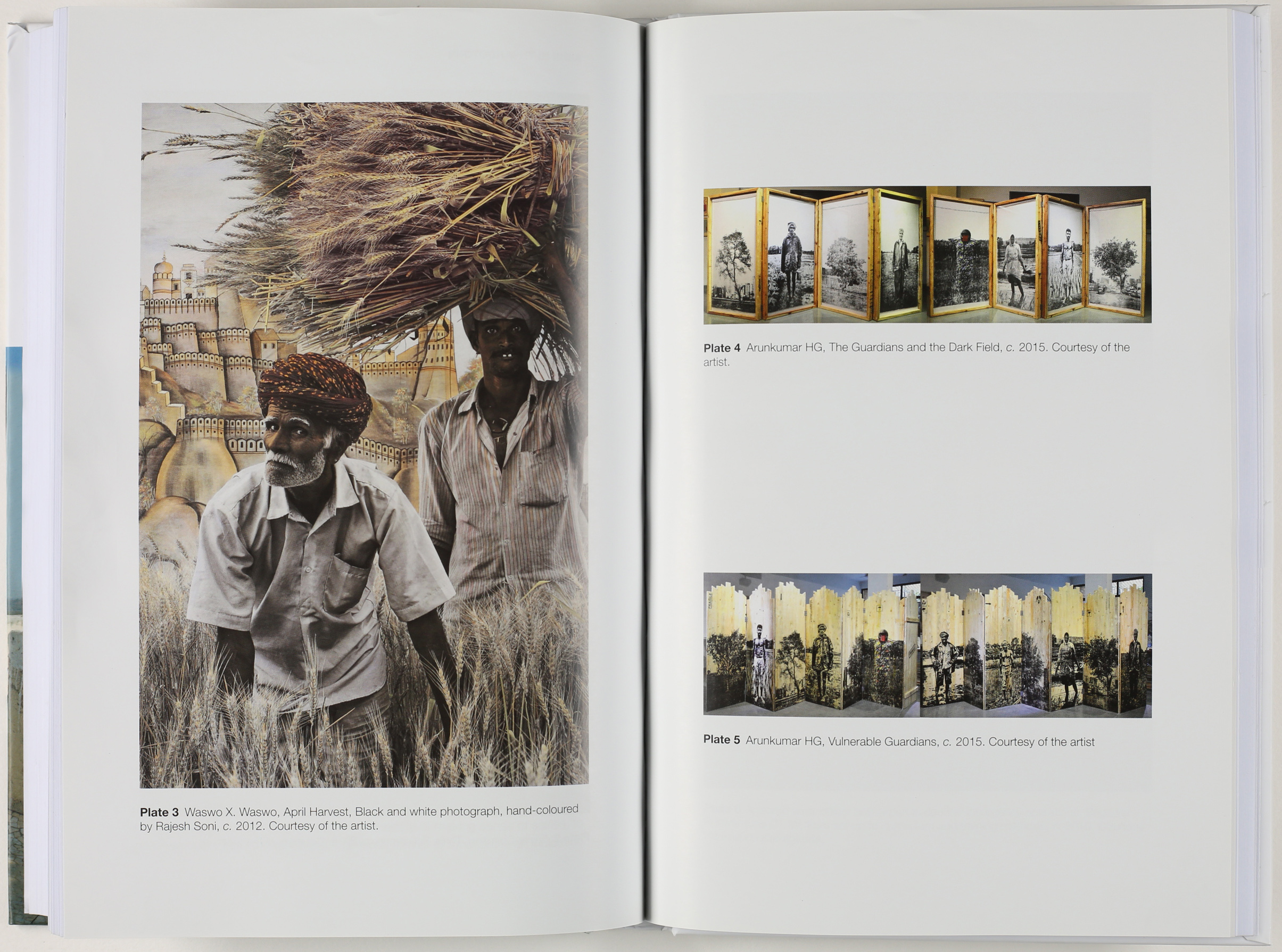

Loosely speaking, contributors to the book’s first section ‘Photographic Time and Memory’ are theoretically concerned with temporalities of photography – taking into account for example how the photograph is indexically joined to the past and simultaneously exists as an object in the present. Inherent in many of the chapters is skepticism around the photograph as an environment hosting a pristine or fully legible past and acknowledgement of the time bound reading of any photograph. This section stands on a different ground to that of scholarship using the archive as a resource with which to establish fixed chronologies pertaining to photography’s invention, its development and key events and people associated with it.

Spread from the publication. Images by Waswo X. Waswo and Arunkumar HG.

The second section of the book – ‘Photographies in Contemporary India’ – acknowledges an expanded notion of photography globally and in the Indian context: new modes of image-making, an ever-increasing range of contexts in which photographic images have agency and a media environment characterised by a culture of sharing, especially of visual content. Accordingly, contributors participate in discussion around computational technology’s expansion of what we mean when we say photography. There’s also a questioning of some of the dualities inherent in the documentary image – the facility with which it, on the one hand, reproduces normative ways of seeing and on the other critiques problematic aspects of Indian society; the scope of the section is able to accommodate a regional government’s turn to documentary photography in the production of narratives of statehood; the global phenomenon of the selfie; the encroachment of computer vision in the Indian space industry and development sector; the place of the algorithm in photo-based artistic practices; the internet’s missing images; photojournalism’s role in trauma experienced by the survivors of communal violence; and how the burden of representation with which documentary photography has been yoked for so long is overturned in photographs that purposefully yield little in the way of ‘productive evidence’ about land and agriculture in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. In bringing together chapters in this section, our concern has been to connect readers with photography’s ever expanding remit in the contemporary moment.

Spread from the publication. Images by Erik Kessels and Chinar Shah

Spread from the publication. Images by Erik Kessels and Chinar Shah

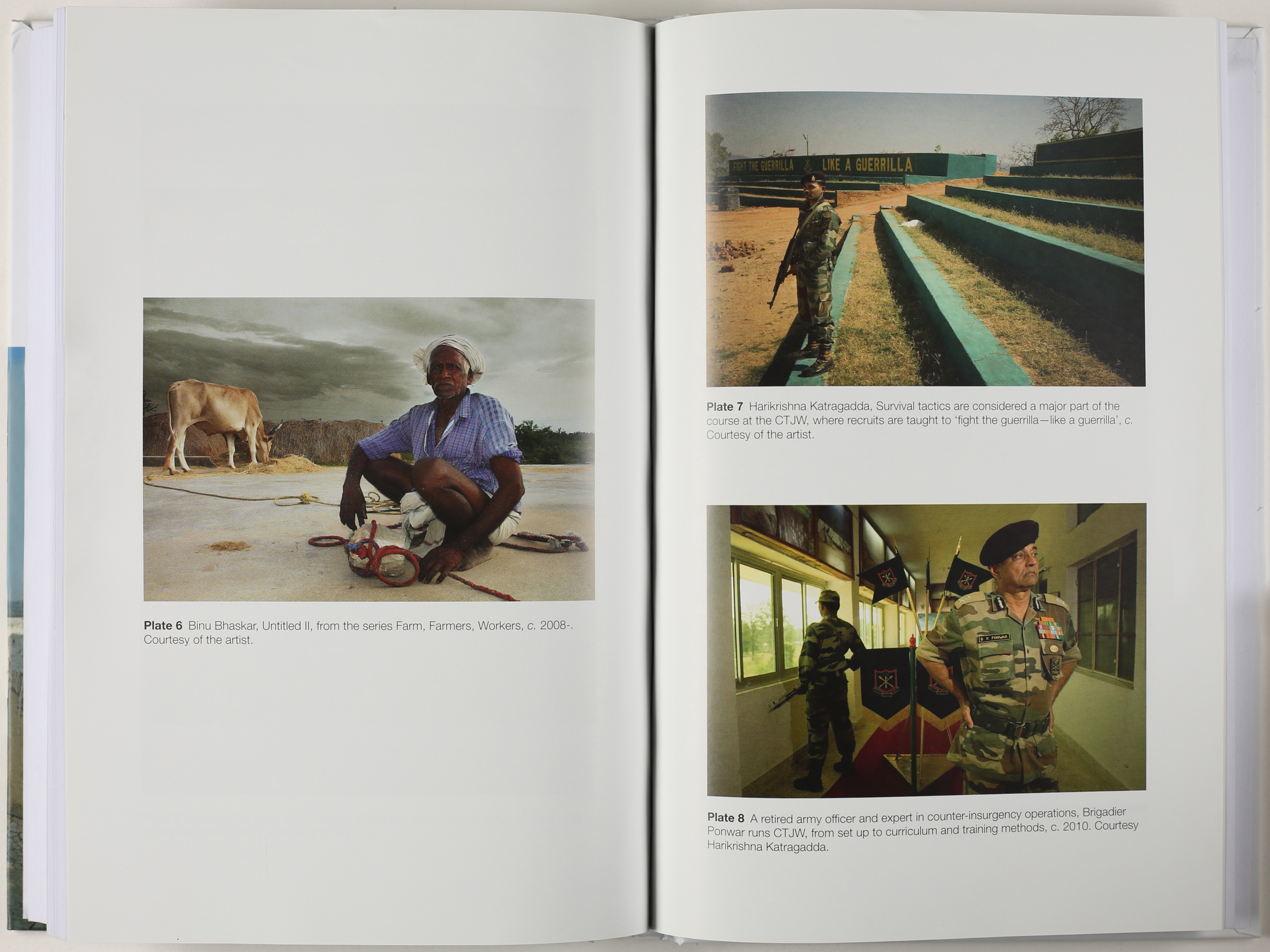

Spread from the publication. Images by Binu Bhaskar and Harikrishna Katragdda

Spread from the publication. Images by Binu Bhaskar and Harikrishna Katragdda

Spread from the publication. Images by Arko Datta and Sebastian D’Souza

Spread from the publication. Images by Arko Datta and Sebastian D’Souza

Aileen Blaney is faculty at Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. She has written on Irish cinema, Indian photography and the digital image in contemporary visual culture for numerous journals and edited collections. She is co-editor of Photography in India: from Archives to Contemporary Practice (Bloomsbury, 2018).

Chinar Shah is an artist, writer, academic and occasional curator. She runs a home gallery called ‘Home Sweet Home’ in Bangalore. She is a co-editor of Photography in India: From Archives to Contemporary Practice, Bloomsbury, UK. Her work ‘Silenced Ruptures’ (2012) on the Gujarat riots has been part of a travelling memorial exhibition around India. Her recent work ‘Aravanis’ (2015) was shown at the Tate Liverpool and subsequently at festivals worldwide including the Birmingham Photo Festival and Art Bengaluru. Chinar has also been part of many international artist exchange programs. She recently received grants from the prestigious Inlaks Shivdasani Foundation and Pronto – Göteborg Stad Kultur of the city of Gothenburg. She studied Literature and Cultural Studies at English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad and later did her PGDP in Photography from NID, Ahmedabad. She currently teaches photography and visual arts at Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore.

Comments